- Visit Us Safely

- Opening Hours

- Getting Here

- Admission and Tickets

- Exhibitions

- Virtual 3D Tour

- Kunstkamera Mobile Guide

- History of the Kunstkamera

- The Kunstkamera: all knowledge of the world in one building

- Establishment of the Kunstkamera in 1714

- The Kunstkamera as part of the Academy of Sciences

- The Kunstkamera building

- First collections

- Peter the Great's trips to Europe

- Acquisition of collections in Europe: Frederik Ruysch, Albert Seba, Joseph-Guichard Duverney

- The Gottorp (Great Academic) globe

- Siberian expedition of Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt

- The Academic detachment of the second Kamchatka expedition (1733-1743)

- 1747 fire in the Kunstkamera

- Fr.-L. Jeallatscbitsch trip to China with a mission of the Academy of Sciences (1753-1756)

- Siberian collections

- Academy of Sciences' expeditions for geographical and economic exploration of Russia (1768-1774)

- Research in the Pacific

- James Cook's collections

- Early Japanese collections

- Russian circumnavigations of the world and collections of the Kunstkamera

- Kunstkamera superintendents

- Explore Collections Online

- Filming and Images Requests FAQs

The Academic detachment of the second Kamchatka expedition (1733-1743)

One of the tasks of the so-called Academic Detachment of the Second Kamchatka Expedition (sometimes called Great Northern Expedition) was gathering scientific collections for the Kunstkamera. The exhibits-to-be of the academic museum were not only to be publicly displayed but also available for further studying. Special instructions were composed for collection gathering. Expedition participants, namely, G.F. Muller, J.G. Gmelin, S.P. Krasheninnikov, G.W. Steller; painters J. H. Berkgan and J. W. Lurcenius and numerous assistants did an excellent job to accomplish the goal.

Set off for Siberia, St. Petersburg academics were sending back to the Academy of Sciences boxes with minerals and ores, ethnographic and archeological gatherings, drawings of animals, fishes, birds, along with stuffed animals, plants and seeds. By evidence of a Swedish scholar Carl Reinhold Berch, who studied antiquities and lived in St. Petersburg since the end of 1735 to May 1736, “transportable antiquities and naturalia” were sent to St. Petersburg; painters were drawing plants and animals “which could not be sent in their natural status from those Tatarian countries,” and the drawings were sent to the Academy of Sciences. Once, Berch became an eye witness of how packages sent from the expedition were ripped open and “saw numerous well stuffed small birds and quadruped animals; all sorts of figures of copper and iron, as well as tools found in burial hills; various idols which pagans still worship in those parts of the country. Some idols looked like faces made of wood or copper; other ones were just made of black sheep skin leveled out on thick felt, decorated with blue pearls sawn in instead of eyes, and cut out fur of top of the head for making some resemblance with a face. Several sets of figures from the border with China carved of stunning translucent stone were most beautiful. Of the clothes, the most unusual seemed to be the mantles of several sorcerers and sorceresses made of rough leather with numerous sawn-in straps hanging down the back and sleeves (almost like footman’s cords) and pieces of metal attached to them; the latter ones were making awful noise. A lot of such hanging straps decorated the headwear <…> and related to them drums”. From the account of the same C.R. Berch, the received items were immediately systematized and placed “by classes in the cabinet of artificial and natural creations.”

Expedition participants had sent 29 “parcels;” for two times, the items brought were delivered directly to St. Petersburg: in February and May of 1743. Since February 18 to February 26, Gmelin and Muller “gave to the Kunstkamera a considerable number of natural things, which they had brought, related to descriptions of peoples and antiquities.” On May 11, 1743, the Academy of Sciences had accepted “antiquities (with inventory),” “clothes of Siberian peoples and other items (with inventory), “a box with stuffed birds,” “a barrel with fishes in wine,” and “a bone of an unknown animal.” In 1748, the Academy obtained from F. Muller ethnographic and archeological items which he had bought “at his personal account” in the course of the expedition.

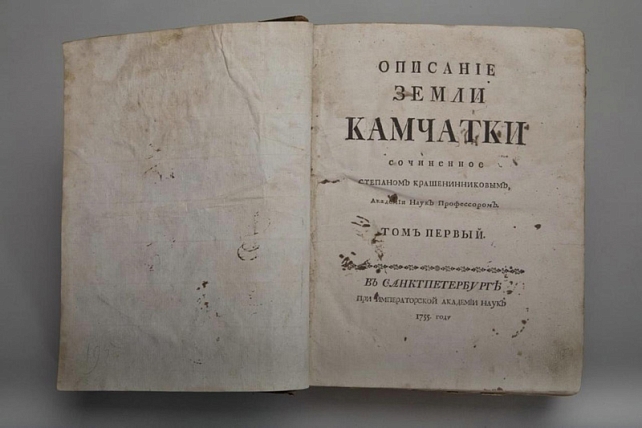

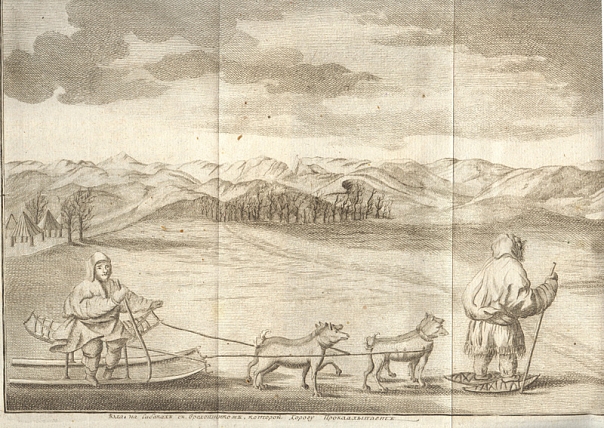

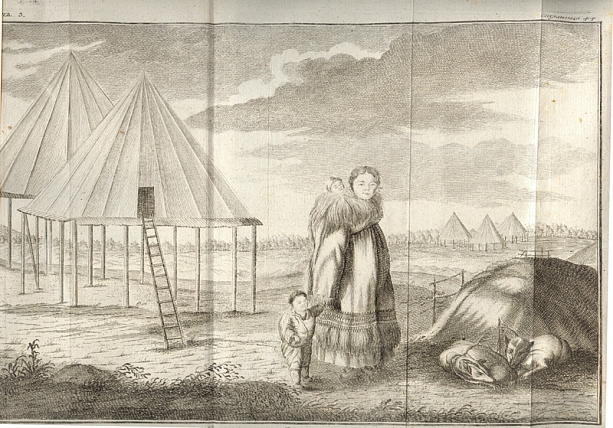

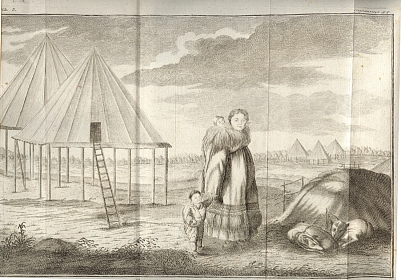

Drawings published in Stepan Krasheninnikov’s book The history of Kamtschatka and the Kurilski Islands with the countries adjacent (SPb., 1755) have major interest for understanding of the novelty of ethnographical studies. They reconstruct with great accuracy not only the clothes and elements of everyday life and occupations of the Kamchatka peoples, but show their anthropological individualities.

Stepan Krasheninnikov’s book de-facto became a European bestseller and was republished in many European languages. The majority of publications had reproductions of engravings from the St. Petersburg edition. Nevertheless, publishers of the 1770 French edition were unsatisfied with these scholarly illustrations and commissioned a prominent French painter, Jean-Baptiste Le Prince (1734-1781), a student of the famous François Boucher, to make new drawings. Their choice was, probably, stipulated with that Le Prince lived in Russia for five years, since 1758, worked at the court of Catherine II, traveled around Finland and Baltic countries, and, therefore, was considered an expert on Russia. A number of paintings was created by painter and engraver Jean-Michel Moreau (le Jeune) (1741-1814), who had also visited Russia in 1758 - 1759 and taught at the Academy of Arts. Based on Le Prince and Moreau’s paintings, engraver J.-B. Tillard (1723-1798) created the engravings. Two famous painters made their drawings based on the subjects of Russian engravings but failed to retain the anthropological types and peculiarities of the housing and landscapes. Comparison of their works with engravings from the St. Petersburg edition of S.P. Krasheninnikov’s book shows only too well the origin of not only ethnography but also anthropology at the Academy of Sciences.