- Visit Us Safely

- Opening Hours

- Getting Here

- Admission and Tickets

- Exhibitions

- Virtual 3D Tour

- Kunstkamera Mobile Guide

- History of the Kunstkamera

- The Kunstkamera: all knowledge of the world in one building

- Establishment of the Kunstkamera in 1714

- The Kunstkamera as part of the Academy of Sciences

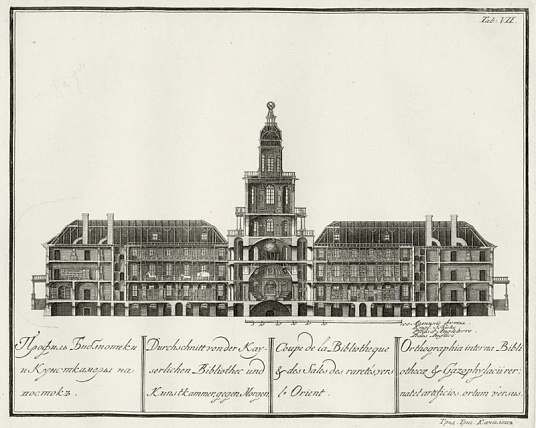

- The Kunstkamera building

- First collections

- Peter the Great's trips to Europe

- Acquisition of collections in Europe: Frederik Ruysch, Albert Seba, Joseph-Guichard Duverney

- The Gottorp (Great Academic) globe

- Siberian expedition of Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt

- The Academic detachment of the second Kamchatka expedition (1733-1743)

- 1747 fire in the Kunstkamera

- Fr.-L. Jeallatscbitsch trip to China with a mission of the Academy of Sciences (1753-1756)

- Siberian collections

- Academy of Sciences' expeditions for geographical and economic exploration of Russia (1768-1774)

- Research in the Pacific

- James Cook's collections

- Early Japanese collections

- Russian circumnavigations of the world and collections of the Kunstkamera

- Kunstkamera superintendents

- Explore Collections Online

- Filming and Images Requests FAQs

The Kunstkamera: all knowledge of the world in one building

If you ask someone what comes to mind when they think of the Kunstkamera, a likely typical response would be a collection of curious objects, of “freaks” and “monsters.” However, in the eighteenth century, the perception of the first public museum in Russia was quite different. The museum was not a mere collection of items but also a repository of man’s knowledge about the world and human beings. Above all, it was a collection of curiosities, but not so much in the sense of something occurring rarely or abnormalities as in the sense of natural developments hidden from human eyes. These secrets of nature, hidden deep in the earth, forests, and fields, on the bottoms of seas and oceans, in myriads of stars above our heads, and even inside our bodies, revealed themselves to the Kunstkamera’s visitor. These museum items, the science previously unknown to an ordinary Russian, and even instruments that helped obtain new knowledge were stored in a specially erected building that holds its name today: the Kunstkamera.

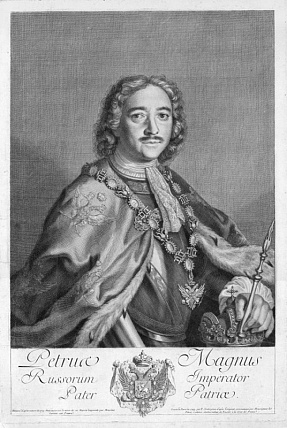

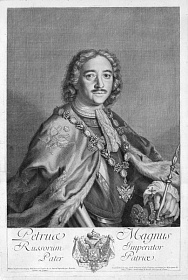

Peter the Great was the founder of the Kunstkamera: his vision guided the museum’s creation, and he put together the museum’s first collections. It was in the time of battles and sweeping reforms aimed at modernizing Russia when books and “naturalia” from the Apothecary Chancery, curiosities from the Tsar’s private collection along with the volumes from the library of the Duke of Holstein were brought from Moscow to the country’s new capital of Saint Petersburg. At first, the collections were stored in one of the first stone buildings in the city – the Summer Palace, built for the Tsar by the architect Domenico Trezzini. In 1714, Peter I appointed his chief physician, a native of Scotland, Robert Erskine, to look after the books and natural curiosities. But since Erskine often accompanied the Tsar in his military expeditions, Peter I hired Johann Daniel Schumacher, an interpreter, and an Alsace native, to put collections in order and prepare them for public display. Johan Schumacher had been in charge of the Kunstkamera and its library for many decades.

Historians believe that the idea of the Kunstkamera came from the experience and impressions acquired by the Russian Tsar during his foreign travels in 1697-1698 and 1717-1718. These trips originated from the political and military interests of Russia. A primary political goal for Russian diplomats, commissioners, publishers, and journalists was to create an image of modernizing Russia. Articles about new Russia appeared on European press pages: in 1706, Journal de Trevoux wrote that muses and sciences were moving up North, where “presently ruling Tsar Peter Alekseyevich had a strong intention to enlighten his state.” The establishment of the museum and the acquisition of valuable collections from leading European curators reinforced Russia’s new image in the European public’s eyes. Peter I had yet another goal for creating the Kunstkamera: he strove to disseminate knowledge and establish the Academy of Sciences and a university. These new institutions aimed at studying the country’s resources and inhabitants and, therefore, were of great national significance.

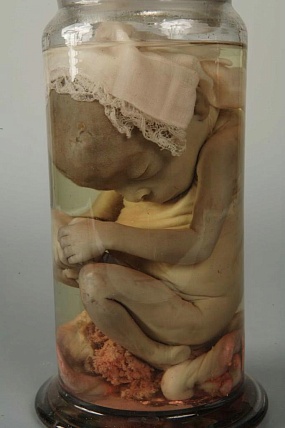

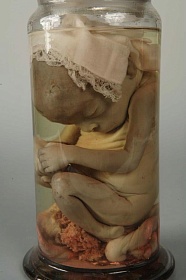

In his decree of 1718, the Tsar ordered to send “born freaks,” i.e., misshapen and deformed children and animals, to St. Petersburg for a fee and imposed a fine for concealing them. These items contributed to the advancement in anatomy and medical science, including battlefield medicine. The same decree mandated to collect and donate “extraordinary stones, human and animal bones, as well as bones of fish and birds, old inscriptions on stones, iron or copper, as well as old and remarkable weapons, plates and dishes, and so on, especially what was extremely old and extraordinary.”

The newly created Kunstkamera was a state-funded museum, a feature distinguishing it from other European collections of a similar type. The 1724 decree on the creation of the Academy of Sciences provided, “In order for the Academy to have no shortages of necessary means, it is necessary that the library and the natural things cabinet of the Academy be opened <...> those books and instruments which the Academy needs should be bought out or made here.” As an academic institution, the Kunstkamera expanded its collections by acquiring objects from state-sponsored research expeditions. The museum accumulated samples of ores and minerals from Russia and abroad, specimens of Russian flora and fauna, the artifacts and religious objects of different peoples in Russia and globally, and findings from “ancient graves.” The museum’s numismatic collection spanned a period from Ancient Rome to the Great Northern War. The Kunstkamera played a crucial role in developing the Russian Academy of Sciences, as it spurred the advancement of ethnography, archaeology, and other disciplines.

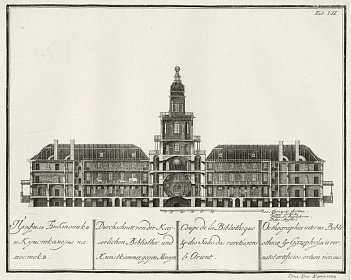

During the first half of the eighteenth century, the Kunstkamera became a state-of-the-art universal museum. Thanks to the surviving documents, and engravings published at that time, we can “walk” through the halls of the museum and the library, which formed a single whole. Visitors reached the Kunstkamera by boat. The entrance was not from Neva’s embankment but from the northern side of the building. After having passed the bindery and the bookstore selling “books of academic print,” the guests found themselves in the lower hall of the library. Forty-six library showcases, which stood along the walls between the windows and around the room’s perimeter, contained books on history, philosophy, rhetoric, mathematics, and geography. On the same floor, there were four showcases, where the assistant librarian kept catalogs of the library and the museum. On the second floor, there were 22 library cases holding books on anatomy, medicine, chemistry, and natural history. The third floor contained books on gardening, architecture, genealogy, optics, hydraulics, atlases and maps, and Chinese, Turkish, and Persian books. One of the showcases contained Russian Academy of Sciences publications, and others had printed books and manuscripts. The library also had a collection of paintings, and the two big globes stood in the second-floor hall.

After passing through the library, visitors entered the Anatomical theater in an amphitheater. Benches were arranged in a semicircle in four sectors, one above the other. Public autopsies were rare: the anatomical theater was mainly used for research, not public performances. Specimens acquired in the course of autopsies by professors and adjuncts were kept in 12 showcases standing in the room. The halls of the Kunstkamera formed an enfilade. Because of this, one could quickly move from the anatomical theatre to a different room where the famous Frederick Ruysch’s anatomical collection was displayed. Showcases along the walls contained preserved anatomical specimens of human organs, such as skin, muscles, brain, etc., and human skeletons stood between the showcases. Other showcases along the interior perimeter of the hal l contained Ruysch and Seba’s zoological samples: “frogs and shell-skinned animals,” “all sorts of lizards,” snakes, fishes, and “various reptiles.” Further along the corridor and to the left, visitors would get into three connected halls containing the mineralogical collection. It comprised rare foreign minerals, but primarily minerals from individual provinces of Russia, such as alum, sulfur, resin, iron, copper, and gold. There were fossils in two cabinets. One of the cabinets contained the model of a mining factory, a testament to the educational character of the Kunstkamera. And opposite the entrance to the third room, the visitor saw a cabinet with shells, and on the sides, “two grottoes of sea stones, herbs, and shells, elaborately composed.” Leaving these halls into the corridor and slightly returning to the right, the visitors entered a chamber with drawings of all things stored in the Kunstkamera, kept in cases shaped as books. Next to it, there was a storeroom where “all sorts of curious and valuable things made of gold, silver, and precious stones” were kept: daggers, necklaces, diadems, horse harnesses, the collection named “Scythian Gold,” golden and silver vessels, and keys to various cities. This room led to the “münz-cabinet,” holding a collection of coins and medals. The numismatic collection was stored in eight cabinets and systematized by country.

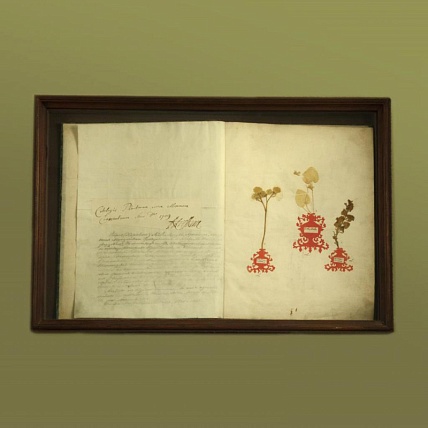

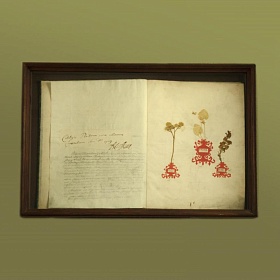

Visitors returning to the Anatomical theatre could then go upstairs to the second floor, where they would find showcases displaying bones and skeletons of animals, including those of a mammoth and a whale, horns of quadrupeds, and other animal skeletons. In the next hall to the left were skeletons of four-footed animals, birds, and plants. The museum used the most advanced taxonomy system of the time to systematize its animal collection. The Kunstkamera acquired a vast botanical collection, including several herbaria from well-known collectors. Fr. Ruysch’s herbarium was organized by the Tournefort principle; G.W. Steller’s herbarium was collected during his Siberian expedition near Irkutsk, and there were three J.G. Gmelin’s collections. Plant collections usually occupied lower parts of the showcases; three cabinets displayed seeds of medicinal herbs.

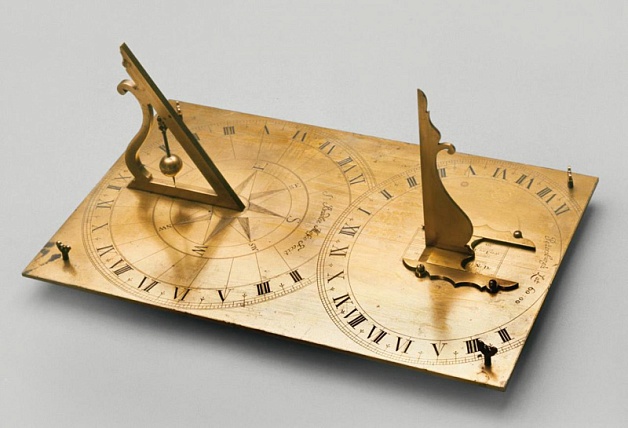

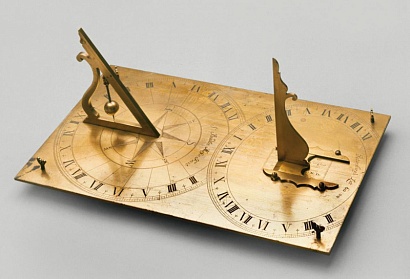

“Peter the Great’s Memorial Cabinet” contained the famous Emperor’s waxwork, his garments, the sword, and other memorial objects. There were also Peter’s “desktop” books on mathematics, shipbuilding, civil and military architecture, and copper engraving. In the three adjoining rooms was Peter the Great’s lathe: the lathes on which he liked to work and some of the things he had chiseled. The gallery upstairs contained works of art: wax and plaster figures, wood, ivory, and stone carvings. The collection of art objects was quite substantial: it occupied ten showcases. On the left side of the gallery, a visitor would see what today would be called an ethnographic collection brought from the expeditions dispatched by the Academy of Sciences. It included clothes of Siberian and other peoples of Russia, religious attributes, such as Shamans’ drums, clothes, and images of gods (“idols”). The Chinese collection was held there as well. Two showcases in the gallery contained archeological findings made of bronze and other non-precious metals. The round hall above the Anatomical theater boasted the famous Gottorp globe. Showcases containing physical, astronomical, and mathematical instruments stood along the walls: they exhibited sundials, orbs, spheres, burning mirrors, and ship models. Three observatories were located above the globe: the lower, the upper big, and the small upper.

Such was the Kunstkamera in its golden age, up until the mid-eighteenth century, embodying Peter the Great’s notions about a universal public and scientific museum, which was unique for the time. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, the Kunstkamera as all-embracing museum ceased to exist. Due to the professionalization of science, specialized museums superseded universal museums. Collections of the Peter’s Kunstkamera formed the foundations of the Zoological, Botanical, Mineralogical, Asiatic, and Ethnographic Museums. Several exhibitions, including anatomical, numismatic, and Egyptian collections, the collection of instruments and paintings, and the Memorial Peter the Great’s Cabinet, were transferred to the Hermitage museum. It was an inevitable development: the Kunstkamera was designed not as a cabinet of curiosities but as a science museum, and it was bound to evolve along with constantly developing scientific knowledge.