- Visit Us Safely

- Opening Hours

- Getting Here

- Admission and Tickets

- Exhibitions

- Virtual 3D Tour

- Kunstkamera Mobile Guide

- History of the Kunstkamera

- The Kunstkamera: all knowledge of the world in one building

- Establishment of the Kunstkamera in 1714

- The Kunstkamera as part of the Academy of Sciences

- The Kunstkamera building

- First collections

- Peter the Great's trips to Europe

- Acquisition of collections in Europe: Frederik Ruysch, Albert Seba, Joseph-Guichard Duverney

- The Gottorp (Great Academic) globe

- Siberian expedition of Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt

- The Academic detachment of the second Kamchatka expedition (1733-1743)

- 1747 fire in the Kunstkamera

- Fr.-L. Jeallatscbitsch trip to China with a mission of the Academy of Sciences (1753-1756)

- Siberian collections

- Academy of Sciences' expeditions for geographical and economic exploration of Russia (1768-1774)

- Research in the Pacific

- James Cook's collections

- Early Japanese collections

- Russian circumnavigations of the world and collections of the Kunstkamera

- Kunstkamera superintendents

- Explore Collections Online

- Filming and Images Requests FAQs

Acquisition of collections in Europe: Frederik Ruysch, Albert Seba, Joseph-Guichard Duverney

Frederik Ruysch (1638 – 1731), world-famous Dutch anatomist, was born in the Hague (the Netherlands) and got education of an apothecary at the University of Franeker in the north of the Netherlands. Already an owner of a pharmacy, he had been continuing education at the Medical School of Leiden University where he was engaged in preparation and conservation of blood vessels and lymph tubes, which became quite popular after William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of blood. His university friend Jan Swammerdam introduced him to the techniques of injections into the blood vessels of a dead body, which he was injecting with liquefied wax. Ruysch had been working on improvement of this technique for a very long time, until he managed to receive astonishing results: his preparations had intra-vital coloration and could be preserved for a very long time.

In 1666, Ruysch was appointed as city anatomist of Amsterdam and began to create his home museum or “Cabinet.”

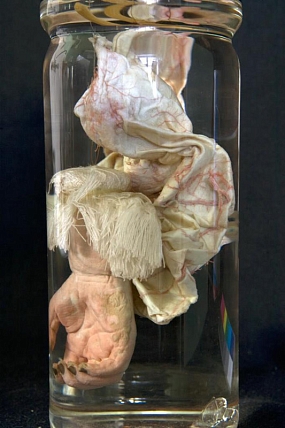

Ruysch sought to decorate his anatomical preparations in such manner that those inspired admiration even among people who had little knowledge in anatomy. He decorated the places of cuts of children’s hands and arms with lace doilies to make them look attractive and not scare off with the look of dead flesh. Into the pink from injections little fingers, sometimes, another small preparation was put, while an embryo could be placed next to the baby’s leg.

F. Ruysch was author of several scientific discoveries. The discovered the embryonic artery of the vitreous body; examined variants of bronchial and pulmonary arteries. These discoveries became possible thanks to perfection of his method of injections penetrating into the finest vessels, which could be seen only microscopically. Contemporaries named the unique anatomist’s method “Ruysch’s art,” and called his home museum “the seventh wonder of the world.”

Peter I, who came to Holland with the Grand Embassy in 1697 and was getting around all places of interest in Amsterdam, could not miss visiting the “Cabinet” of Frederic Ruysch. On September 17, 1697, he asked Mayor of Amsterdam Nicolaes Witsen to introduce him to world-famous 60-year old Ruysch. The huge anatomical collection in Ruysch’s home museum-cabinet at 15 Bloemgracht Canal produced a strong impression of Peter. He made the following inscription in the visitor’s book: “I, the undersigned, during the journey purposed to see the major part of Europe, have visited Amsterdam to gain knowledge, the need in which I have always had, reviewed here the things, among which I, not the least, could see Mr. Ryusch’s art in anatomy and, as is customary in this house, have signed this in person. Peter.” Alexander Menshikov signed below.

Nearly 20 years later, in January 1716, Tsar Peter undertook his second trip abroad. With great interest he carefully inspected Ryusch’s increased collections and, told that Ryusch wanted to sell them, assigned his Archiater (Chief Physician) Robert Erskine to hold negotiations. The entire collection of more than 2000 preparations on embryology and human anatomy and 1179 specimens of small mammals, reptiles, and insects, 259 birds preserved by dry method, two showcases with herbariums and a big number of boxes with butterflies, sea animals, and shells, i.e., nearly everything included in Ryusch’s first ten catalogues, was purchased for 30,000 guilders and shipped to Russia.

On February 14, 1716, Peter I ordered to acquire the collection of Amsterdam apothecary Albert Seba. It arrived in St. Petersburg on September 2 of the same year. Seba’s collection included both naturalia, mostly from South America, and pieces of art brought from Japan, China, and South America. Among the zoological exhibits, there were various fishes, snakes, including an anaconda presently exhibited in the Zoological Museum, lizards, a pipa-toad, and stuffed sloth, flying possum, and anteater. Thanks to the purchase of Seba’s collection, Kunstkamera’s funds were added with Chinese cloth items, Japanese works of art, and weapons (kris dagger).

In February 1721, Johann Daniel Schumacher, Peter I’s librarian and the “Kunstkamera Superintendent” traveled to Germany, France, England, and Holland. He traveled for personal reasons, but along with Peter’s permission to leave Russia, the librarian received several important tasks from both the Tsar himself and Chief Physician L.L. Blumentrost. Besides contacting European academics, Schumacher was obliged to visit museums and libraries, in order to “notice” the order and principles of exhibiting of collections, and how they differed from the Peter the Great’s “Imperial Cabinet” and what was missing in the latter and could be acquired.

Of the acquisitions, important for the museum were mathematical and research instruments bought in France and Holland; camera-obscuras and laterna magicas in Holland and part of J. Lueders’s Münz Cabinet in Hamburg which laid foundation to the Kunstkamera’s collection of ancient coins (another part of Lueders’s collection was bought for the Kunstkamera later, in 1738). At an auction in Holland, J.D. Schumacher bought several pieces from N. Chevalier’s cabinet: gemmae, ancient lamps, two cylindrical mirrors, several ancient flutes. At another auction, along with Pieter de la Court, also known to Peter, he acquired a greenhouse and paintings, as “for the new library and Kunstkamera henceforth paintings will be of great need.”

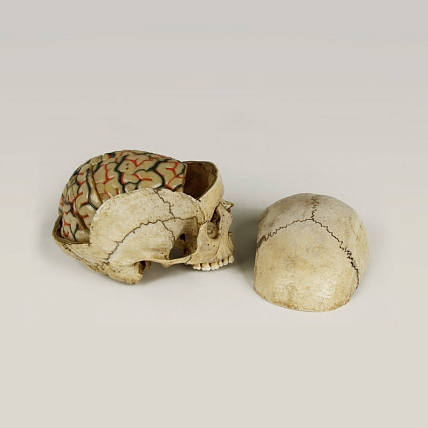

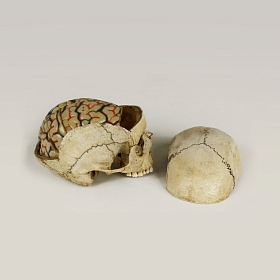

Among many assignments given to J.D. Schumacher prior to his trip to Europe, he got a task to receive and bring to Russia wax anatomical models which R. Erskine had ordered in Paris. Such models appeared in the very end of the 17th century and were on high demand, because they very much facilitated the teaching and learning of anatomy.

In the inventories of collections of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), under № 5018-2 is listed a wax model of the brain in a real skull purchased by Schumacher from French anatomist Joseph-Guichard Du Verney in 1722.